“Two Fates” and “Wolfhunt” Slavic & East European

Slavic & East European Journal review 10/19/16 (p. 578-581)

by Dr. Thomas Garza

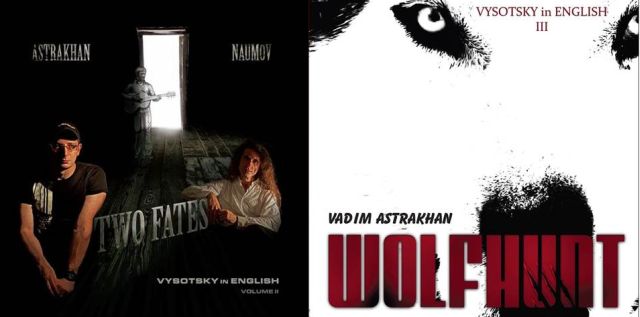

Vadim Astrakhan and Yuri Naumov. “Two Fates. Vysotsky in English: Volume II.” CD.

Vadim Astrakhan. “Wolfhunt. Vysotsky in English: Volume III.” CD.

The rarified domain of successful literary translation requires, in addition to native proficiency in the language into which the work is being rendered, native or near-native competence in the language from which the work is being translated. Furthermore, the successful translator not only is bilingual, but also bicultural, able to convey embedded cultural references and connotations that abound in a work of literature. Thus, most translators translate into their native language, in order to create a faithful linguistic and metalinguistic rendition of the original work. In the realm of translation from Russian to English, there have been notable exceptions; Vladimir Nabokov was uniquely adept at rendering into lively and idiomatic English Russian literary texts such as Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin.

The work and performances of bard, poet, and actor Vladimir Vysotsky occupy a unique place in Russian culture and byt, or mores of daily life, defying, as many purists contend, accurate translation into any language. Nonetheless, numerous translators have taken on the daunting task of rendering the linguistically complex and culturally embedded lyrics of Vysotsky into English and other world languages. Indeed, a recent volume, Vladimir Vysotsky in New Translations: International Poetic Project (Polish Vladimir Vysotsky Museum, 2014), compiled and edited by the late Marlena Zimna, includes translations into fifty-nine native languages (but not English!) of sixty-three poets and translators. Yet translators of Vysotsky’s works into English have most often been native speakers of Russian, most notably Sergei Roy, whose translations appear on the official Vladimir Vysotsky website (http://www.kulichki.com/vv/eng/), and Andrey Kneller, translator of the self-published Unfinished Flight: Selected Songs of Vladimir Vysotsky (2010).

Continuing this tradition of Russians translating Vysotsky into English is Vadim Astrakhan, who emigrated to the U.S. from Russia in 1991. Though his first translations of Vysotsky into English appeared soon after his emigration, he began to perform and orchestrate his own translations less than a decade ago and to record these performances only in 2008. He also created and maintains a website, “Vladimir Vysotsky in English: A Project by Vadim Astrakhan” (www.vvinenglish.com), which contains links to his music, texts of his translations, press releases, videos, and other news regarding his project. His published audio recordings to date comprise three albums: Singer, Sailor, Soldier, Spirit (2008), Two Fates (2012), and Wolfhunt (2014). This review concerns the two most recent recordings, the renditions of the songs’ lyrics into English, and their performance musically.

Two Fates was recorded over three years (2009–2012) in collaboration with blues singer/ guitarist and compatriot in emigration, Yuri Naumov. With material recorded in seven studios around the world, Astrakhan states that the philosophy behind Two Fates is to “[m]ake the music on the same level as the poetry” (website). To this end, Astrakhan brings in international musicians, including Leonid Verman, John Macaluso, Vladimir Ponomarev, Lex Plotnikoff, and even the Ural State Conservatory Symphonic Orchestra to raise the level of the musical performances, and the album does, indeed, showcase among its tracks some of Vysotsky’s most revered and iconic lyrics, most notably “If Your Friend” and “He Did Not Return from the Battle.”

The most marked feature of the Two Fates album is the variety of musical genres explored in the performances of the various songs. Several of its tracks attempt to preserve the unique guitar/ vocal ensemble of Vysotsky’s original performances, in particular “Tale of a Wild Boar,” “Gypsy Blues,” and “When the Great Flood Waters Had Subsided.” Other songs, like “Race to the Horizon,” “Fireride,” and “Death Convoy,” are performed in styles ranging from hard rock to heavy metal. A strong bass line begins “A Merry Funeral Song,” which then blends into a pop-infused cabaret melody. Perhaps most striking is how the playful, light original performance of Vysotsky’s satirical “Captain Cook” is transformed into a samba-beat ballad about natives who “got the munchies” and cannibalized Cook. The exploration of the multiple interpretations of Vysotsky’s melodies is interesting, if unexpected, for listeners unprepared to hear his well-known works performed in styles different from the traditional manner of the Russian “singer/songwriter” (“avtorskaia pesnia”).

Vysotsky enthusiasts and scholars may find some of Astrakhan’s artistic and musical choices more challenging in his re-imagining of certain songs of the bard, most notably in this CD volume, “Fireride.” From the neologistic title (which is not explained in the lyrics), to the choice of heavy metal as the performance genre, Astrakhan pushes the sensibilities of his listeners to consider alternative interpretations of classic Vysotsky works. In this case, Astrakhan builds on metal classics about war, such as Motörhead’s “Dogs of War,” Metallica’s “One,” and Iron Maiden’s “The Trooper,” to lend a western sound to Vysotsky’s lyrics. The song, about the Russian civil war in Ukraine, was originally written for the 1979 film Forget the Word ‘Death’ (Zabud’te slovo ‘smert’’), but never included in the soundtrack. Though the album was released just as the current tensions between Russia and Ukraine were developing, the song turns out to be as relevant today as when it was originally written.

In terms of his English-language renditions, Astrakhan strives to create verses that mimic in meter and rhyme those of the original Russian lyrics—a quite daunting task given how different the acoustic and stress patterns are in the two languages. Predictably, adherence to the original versification can lead to some questionable choices of diction, syntax, and word collocation. For example, in “He Didn’t Return from the Battle,” the first two stanzas are rendered:

Почему все не так? Вроде все как всегда:

То же небо—опять голубое,

Тот же лес, тот же воздух и та же вода,

Только он не вернулся из боя.

Мне теперь не понять, кто же прав был из нас

В наших спорах без сна и покоя.

Мне не стало хватать его только сейчас,

Когда он не вернулся из боя.

It’s a beautiful day. Why is everything wrong?

And it feels like it will not get better.

Same forest, same river, same air on my tongue…

But he didn’t return from the battle.

Now it doesn’t matter, which one of us won

Our arguments, quarrels … our prattles.

Only now do I miss him, now when he’s gone,

When he didn’t return from the battle.

While one may question the choice to invert the phrasing of the first line, the rhyme of “won” with “gone,” or the use of the definite article with “battle” in the title and lyrics, it is the diction of the translation that most reveals the difficulty of replicating the versification of the original lines, e.g., “prattles/battle.” Russian soldiers in battle engaging in “prattle” may be difficult to imagine, even if the words do rhyme. But Astrakhan does succeed in creating for the Anglophone listener the frame and content of one of Vysotsky’s most iconic verses from his war cycle.

It is difficult to listen to any performance of a Vysotsky song and not notice how the singer chooses to address vocally the unique qualities of his voice, phrasing, and articulation. Astrakhan has often stated in interviews that he does not imitate, but rather interprets his translations of Vysotsky’s songs in performance. Thus, to compare his renditions of Vysotsky’s songs to their original performance is futile; however, given Astrakhan’s choices of musical genre, tempo, and instrumentation, it is appropriate to examine the effectiveness of his performances in their ability to convey the meaning of each song’s lyrics effectively and memorably.

The third album published by Astrakhan is Wolfhunt, recorded between 2011 and 2014, again in both Russian and U.S. venues. On his website, Astrakhan states that this album “contains wild experimentation with a variety of musical genres, including full symphonic orchestra, hip hop, metal, blues, and tango, but keeps closer to the Vysotsky’s [sic] originals” (online). Besides the promised variety of musical styles, Wolfhunt contains several songs that represent complete re-imaginings of Vysotsky’s work, most notably Astrakhan’s revision of the wickedly satirical Soviet-era paean to the life of a low-skilled laborer, “Ia byl slesar’ shestogo razriada” (“I Was a Sixth-Class Mechanic”) into, as the title indicates, a contemporary take on a computer technician’s dreary life. What is absent from this modern, bluesy version is Vysotsky’s ironic humor, with sarcasm and vitriol in its stead. In this case, what is lost in translation is not individual phrases or words, but rather the Soviet-era context that is inextricably intertwined with so many of Vysotsky’s songs of daily life.

More successful as a contemporary update is “So Hazy,” which features the vocals of Russian singer Polina and a Latin-infused beat.

Так дымно, что в зеркале нет отраженья

И даже напротив не видно лица,

И пары успели устать от круженья,

И все-таки я допою до конца!

Все нужные ноты давно сыграли,

Сгорело, погасло вино в бокале,

Минутный порыв говорить пропал,

И лучше мне молча допить бокал.

It’s so hazy, the mirror’s reluctant to show reflection.

I can’t see my face, I can only pretend.

And dancers are tired of feigning affection.

But still I must sing my song to the end.

All notes have already been played in flashes.

The wine in the glass has burned down to ashes.

The fleeting desire to speak has passed,

And now I should quietly drink my glass.

Both the translation and the re-scoring of the music to reflect a more contemporary sound work harmoniously to create a composition that is quite faithful to the Vysotsky original. Wolfhunt also contains the track “The Airfight III,” or “Vsiu voinu pod zaviazku,” which Astrakhan sings in his native Russian. It is, perhaps, in this unique performance that the singer’s real dedication and devotion to the work and legacy of Vladimir Vysotsky is most evident. Here, he faithfully interprets the bard without imitation or falseness. The track showcases not only Astrakhan’s musicality, but also his ability to imbue the classic words of Vysotsky with relevance and authenticity for contemporary audiences.

While both albums include songs whose lyrics do not always convey the essential meaning of the original texts, or whose musical arrangements are innovative but sometimes inappropriate, Two Fates and Wolfhunt represent a rare and impressive effort to bring the works and world of Vladimir Vysotsky to an English-speaking audience. From initiates to the world of the Russian singer-songwriter, to seasoned fans of the bard’s lyrics and music, listeners of Astrakhan’s works will gain additional understanding from his varied and energetic translations and performances of some of the most recognizable songs of the Soviet era.

Thomas J. Garza, University of Texas at Austin